This year marks 50 years of NAIDOC Week

– five decades of celebrating the strength, vision and legacy of First Nations people.

In 2025, the theme “The Next Generation: Strength, Vision & Legacy” calls on all of us to recognise the trailblazers who came before, celebrate the powerful leaders of today, and support those forging the path forward.

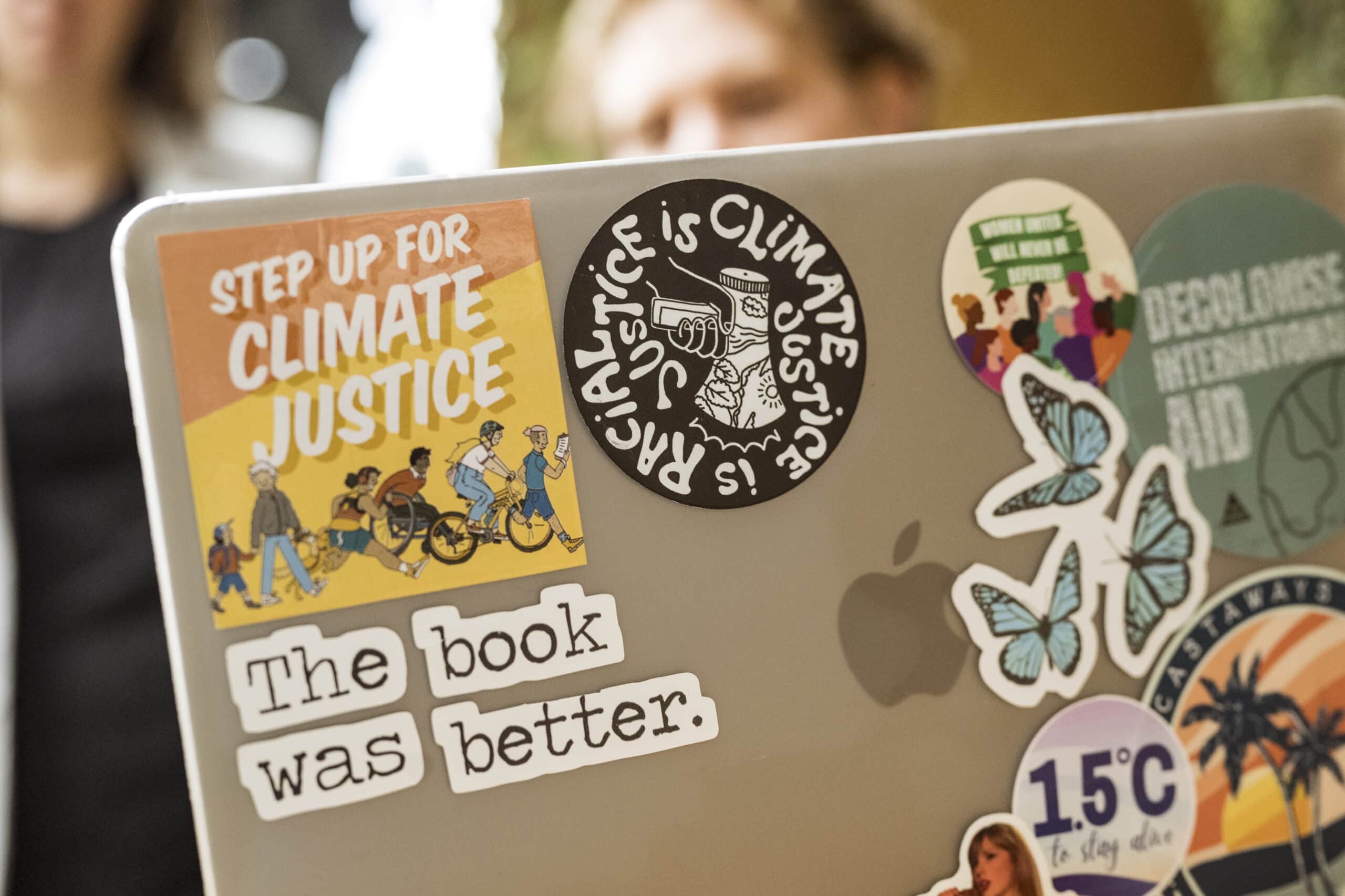

Zhanāe Dodd is a member of Generation Justice and an exceptional young advocate for First Nations justice and climate justice.

This week, she shares her unique perspective and lived experience, bringing fierce commitment, sharp insight and deep cultural grounding to some of the most urgent issues facing our communities and climate today. Zhanāe is a leader, listener, organiser and storyteller – she is helping to shape the just future we all deserve.

Zhanāe is a proud Aboriginal woman from the Ghungalu, Wadja, Kaanju, Birri, Wiri and Wungun peoples. Zhanāe grew up on Darumbal Country in Rockhampton and recently moved to Meanjin/Brisbane, where she is about to begin a double degree in Human Rights and Law.

Zhanāe is the founder and director of several start-ups that centre First Nations knowledges and storytelling, alongside her work as a cultural leader and advocate for justice and climate action. An EJA client, she is a co-complainant in Generation Justice’s human rights complaint against the Australian government, made to the UN special rapporteur on climate change.

This year is the 50th year of NAIDOC, what does this mean to you?

Fifty years of NAIDOC is massive, much has changed over that time. It makes me reflect on how far we’ve come, but also on how much still lies ahead.

My grandfather was born on the side of a Baralaba cotton field and his family were moved to Warabinda mission. On the other side, family were forcibly removed to Palm Island. My family’s recent history is tied up with colonisation, with our culture being demonised and practicing it prohibited. Now, I’m a part of a generation reawakening what was put to sleep during colonisation.

To me, strength is not just about surviving, it’s about thriving. That comes through in our ceremony, in how we care for each other, and how we lead.

NAIDOC is always a busy time for me, with my cultural duties. I’m very actively thinking about legacy: how do we honour it, dream bigger than others could (because they have been held back by so many impacts of colonisation), and build something strong for the generations that come after!

Of course, this is a responsibility that’s much bigger than just one week, and Gen Z! The challenge for everyone is carrying this work and energy through the whole year.

How do you feel your connection to your culture has shaped you today?

Culture isn’t something I do – it’s who I am. I’m a songwoman and storyteller. Because of the impact of colonisation, my parents didn’t receive the full teachings, but now my cousins and I are choosing to relearn and re-teach what was lost. It feels like a return. I’ve learned to dance, sing, weave emu feather skirts and care for Country in many ways.

I’m learning my role in my clan group and the gifts passed down by my old people. That’s opened doors for my mum too. Though she taught me my dreaming stories and so much of my cultural foundations, I was the one who took her out on our Blackdown Country for the first time. Being there made everything click. It was healing.

When I went out most recently, it was us all sitting around a fire with Elders, cousins, and babies, I remember thinking: this is how it was always supposed to be. This is what was taken from us. This is where we feel whole.

You’ve spoken in the past – including in your UN complaint as part of Generation Justice – about how Country keeps score. How does this guide your response to the climate crisis?

Country is always listening. When we talk to her, she responds. When we ignore her, she wails and grieves. She’s a living, breathing being. If you care for her, she’ll care for you.

First Nations peoples have long cared for these lands without visibly impacting them. And that’s different from other places around the world, think of the Pyramids or the Colosseum.

On our Country, you don’t always see what we’ve done, because we have lived with the land, not just on it.

Today, we’ve trusted the Australian government to protect Country, but they’ve failed us. When people say “natural disasters,” often it’s Country screaming because no one listened to her whispers. We need to stop making Country yell for help – and start listening again.

What would you like people to understand about the relationship between climate justice and First Nations justice?

You can’t have climate justice without First Nations justice. If our cultures aren’t respected, if our knowledges aren’t valued, how can there be climate justice?

You can’t exclude the original caretakers of Country and expect a healthy outcome. We’ve been, and are, excluded through land rights injustices, incarceration, family removals, health inequity – systemic approaches to the cutting down or out of our knowledges. How can we pass them on if we’re locked up, taken away from family, dying younger than the rest of the population and barricaded from Country?

Then there’s the fact our knowledges are often dismissed because they doesn’t come with a degree. But some things we do are second nature, common sense, because we’ve practised them for so long.

Allyship here matters, but it includes knowing when to step back and let us lead. We’ve seen in Pacific nations how centring Indigenous knowledges shifts climate priorities for the better. We need that here too.

Through your start-ups, you’re embarking on really innovative, culturally-led work, can you tell us more about this?

Through Burri Energy (Burri means ‘fire’ in my language), I’m exploring sustainable carbon capture using cultural resources like ochre and limestone. Through the consultancy I co-founded, Guyala Yimba (“sweetheart, listen!”), I’m working to support culturally grounded leadership and amplify First Nations stories. And lastly, through Yoora Maltha, with my co-founders, I’m advocating for systemic change and protections for communities failed by existing structures. One big goal is pushing for a national human rights bill.

All of this work is about rebalancing power and returning to Country.

What you think would it look like for Aboriginal wisdom to truly lead climate solutions in Australia?

I think things would look very different!

Firstly, a lot of us mob don’t even realise we’re working in climate spaces because it’s just who we are. I didn’t think of myself as a climate advocate until I joined Generation Justice and started telling my story, and realised, “oh, I’m already doing this kind of work!”

Imagine if we all had full access to our lands, programs to revitalise traditional care for Country – revitalising waterways, bringing back wildlife, performing cool, seasonal burns – and I’m not just talking about a few jobs in national parks, but widespread community-based practises. Everywhere!

Colonisation and capitalism go hand-in-hand, and they’ve been the most damaging things for our environment. But it’s not too late. We can choose another way.

We definitely can! Sometimes it is easy to feel deflated, less optimistic though. What keeps you grounded when the work gets heavy?

My old people – those Elders here and those ancestors who’ve passed – and my connection to spirit. Without it, I wouldn’t be well.

I’ve faced racism, lateral violence, burnout, and a lot of systemic barriers. But I’m never alone. I carry so many with me.

I’d say cultural practices and ceremony keep me strong. They have always helped us move grief through our bodies. I tell people we’re the first somatic practitioners! Singing and dancing keeps me well.

What kind of future do you hope to see in 2075?

Honesty, I hope I’ve done myself out of a job! I hope the systems look after us by default – that we don’t need to fight for our rights, because they’re already upheld. I hope we’re not having the same conversations during NAIDOC Week another 50 years from now!

I want to be an old woman watching my family live with joy – not carrying the burden of the fight. I want our waters to flow freely, our ecosystems to be balanced.

Country to be thriving, and for that connection to always be there. That’s the future I’m fighting for.

What do you think are some of the biggest barriers facing young First Nations leaders today, and what support would make a difference?

Lateral violence is one. It’s like the crabs in a bucket analogy: someone tries to rise and others pull them down. This comes from the survival mindset we were forced into through colonisation. It’s heartbreaking; we need to heal this.

Second, our generation is carrying trauma while also trying to rebuild and lead. That’s heavy. Our generation has been leaning into healing more than ever and the entrenched fight happening parallel to this is a challenging space to navigate.

Lastly, is cultural time vs capitalist time. Our cultures rely on consensus. That takes time. But Western systems run on funding cycles, election terms, strict, short deadlines. We need systems to slow down, to come to the table we’ve built, and respect our processes.

What’s your message for other young First Nations people, and allies reading this during NAIDOC Week?

For mob, I’d say you need to know where you’re from to know where you’re going. Even if you don’t know your Country or your ancestors, they know you. Dip your toe into culture and soon you’ll be swimming!

And for our allies, letting us shine doesn’t dim your light. Know when to lean in and when to lean out – to make space. I can’t always describe what makes a good ally, but I can feel it. It’s when someone brings that good energy, good spirit. It’s not performative, it’s real.