This year marks 50 years of NAIDOC Week

– five decades of celebrating the strength, vision and legacy of First Nations people.

In 2025, the theme “The Next Generation: Strength, Vision & Legacy” calls on all of us to recognise the trailblazers who came before, celebrate the powerful leaders of today, and support those forging the path forward.

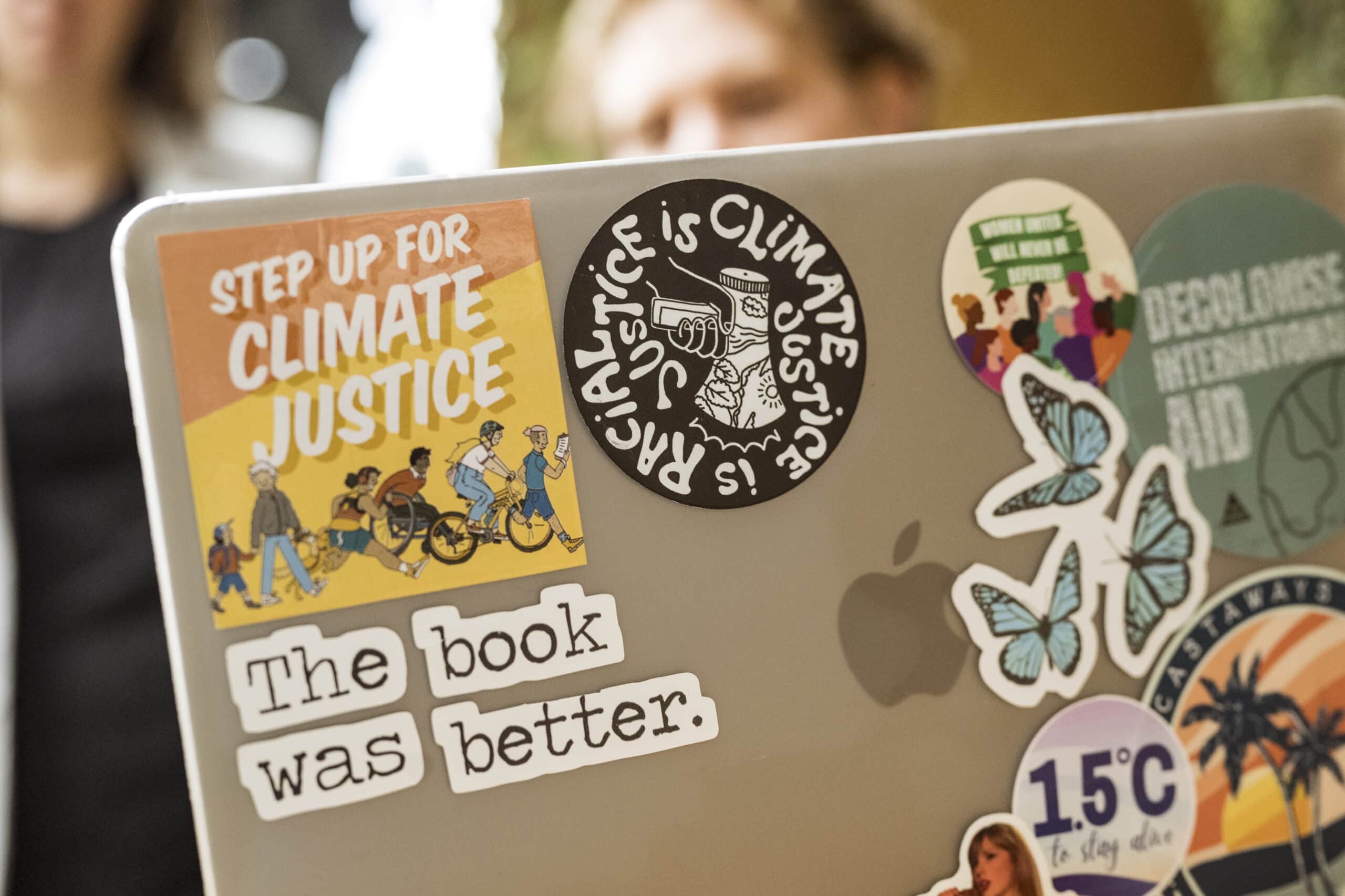

Connor Wright is part of Generation Justice – a proud young First Nations leader and a powerful voice for climate justice.

This week, he shares his story and his vision. Grounded in culture and community, Connor brings courage, clarity and care to the fight for a fairer future. He’s an academic, a speaker, a connector and a changemaker – helping lead the way toward justice for people and planet.

A proud Larrakia man, Connor is a researcher, climate advocate and a co-complainant in Generation Justice’s human rights complaint against the Australian government, made to the UN special rapporteur on climate change.

Growing up on Larrakia Country in Garramilla/Darwin, he now lives and works on Wurundjeri Country in Naarm/Melbourne, where he is completing a Master’s of Environment.

What does this year’s NAIDOC theme: “The Next Generation: Strength, Vision & Legacy” – mean to you?

This year’s theme speaks to recognising and appreciating all the work our Elders have done: the massive contributions they’ve made and the achievements of so many First Nations people.

But it also doesn’t detract from what still needs to be done, and how we, as the next generation, need to build on those achievements and continue their legacy.

I’ve met so many amazing young people from different mobs around Australia. I feel inspired, even if in a particular moment I’m not the one doing something, I know someone out there is. There are so many deadly Indigenous activists, academics, and community leaders doing this work.

How did growing up on Larrakia Country shape who you are today?

I grew up in Garramilla/Darwin with my family – fishing, swimming, spending time with my grandmother, aunties and uncles. We’d head out bush, or to the beach, and collect longbums, periwinkles and mudcrabs in the mangroves. Then we’d cook them over the fire, and sit around sharing stories.

This taught me how connected we are to the environment. There’s a Western framing where people view themselves as separate from nature, especially in cities. But Country taught me how interconnected everything is, and how delicate those systems are.

Take seasonal calendars as an example. We mark seasons not just by weather, but by environmental markers – like barramundi breeding season. That’s how we know what time of year it is. If you went to the desert, there’s no barramundi there, so their seasonal knowledge is shaped by the unique context.

Western calendars just number the days, but ours are rooted in our surroundings. A change in the environment changes our cultural context.

When climate change disrupts those patterns, it doesn’t just affect the environment, it disrupts our culture.

We see ourselves as a part of the environment, not separate or above it. For example, my grandmother always says, “That’s my Country” when she talks about family. I’m not living on Larrakia Country right now, I’m in Naarm/Melbourne finishing my degree, but my sister is down here with me, so that’s my Country too. In this way, I never feel like I’m away from Country.

How did you get involved in advocacy and policy work?

I worked in environmental consulting for two years, mostly auditing for gas companies. Everything I saw was technically legal, but the emissions were so shocking. When you see the scale of emissions from just one site, it’s mind-blowing.

Australia gains so little benefit from these industries, and there is no equity for Indigenous people, despite the extraction happening on our land and waters.

I don’t want to see more fossil fuels projects, but I do want equity and co-design in green energy projects happening on Country.

In your statement as part of Generation Justice’s complaint to the UN, you’ve said climate change feels like a second wave of colonisation. What do you mean by that?

When the environment changes so quickly, we can’t practise our culture in the timeframes we traditionally would. That damages our relationship with Country and interrupts the way knowledge is passed down. A lot of our culture is verbal, through storytelling and practise. If we can’t practise in the proper way or time, culture and knowledge get lost. That’s what I’d call a second wave of colonisation.

Climate change, caused mostly by colonial systems, is now destroying the culture of people who have contributed the least to it.

What we do now will echo into the future. I’ve just submitted my thesis, where I looked at how Indigenous people in Australia can be meaningfully engaged in national climate policy and decision-making. It builds on the work of other mob, intellectual Elders, and proposes a new framework for engagement. It’s about moving beyond financials, to co-design from conception to implementation, so that cultural values are respected.

At the moment, engagement is often tokenistic and box-ticking. That needs to change. I hope to develop this work further, to centre real voices from across Country. Ideally, a framework like this would eventually be embedded in law.

Thinking ahead to 2075, what kind of world do you hope the next generation inherits?

I want a world that’s addressed colonisation, where truth telling is part of our national fabric. I want a just transition: a world without fossil fuels, and a system where we’ve fixed things and no one’s been left behind. I want our kids, my nieces and nephews to look back to now and say: “that was a crazy, dangerous time – but we set things right”.

I want to be an Elder who can say: “we did what we could, what needed to be done, and we did it together”.

And when we are making this necessary transition to a greener future, I think it’s so important that we don’t carry over the same inequities of the current system. That means bringing along people who’ve been harmed by colonisation and capitalism.

Right now, things like gas and coal projects can go ahead, and even if Elders object, they can be vetoed. We need real protections and real self-determination. First Nations people must be involved in designing the new systems from the ground up.

What gives you hope in this complex, long-term work?

Knowing I’m not alone in this. I see so many deadly mob doing amazing things: organising, educating, leading change.

Being a part of groups like the Wattle Fellowship and Generation Justice, alongside Zhanāe and seven other really inspiring young people, helps me carry the weight. Seeing that kind of strength and vision keeps me going.

What’s your message to other young mob, and allies, who are committed to First Nations justice and climate action?

Stay true to your values. Think about the kind of Elder you want to be.

And find community – whether it’s where you live or online. It’s easier to do this work when you can lean on others and ask for help. You’re not alone.

What’s your message for other young First Nations people, and allies reading this during NAIDOC Week?

For mob, I’d say you need to know where you’re from to know where you’re going. Even if you don’t know your Country or your ancestors, they know you. Dip your toe into culture and soon you’ll be swimming!

And for our allies, letting us shine doesn’t dim your light. Know when to lean in and when to lean out – to make space. I can’t always describe what makes a good ally, but I can feel it. It’s when someone brings that good energy, good spirit. It’s not performative, it’s real.